A young couple with two children and a grandmother chose Kazyuo Sejima to be their architect. They valued her for being the author of works of architecture that was “light, clean and white, no bravado at all,” qualities that they thought would help to find the right tension between the privacy found in a dwelling and the public character of a house in a garden. “A shelter for the mind” and “a place to enjoy the blossoming plum trees in the garden”; these were the family’s wishes when they commissioned the house.

Questioning pre-established modes of divisions and hierarchies.

The copy-writer Miyako Maekita, and her husband who is an advertising film producer, had a small site in a neighbourhood close to Tokyo. It was a site of only 92.30 m2 where beautiful plum trees and wild flowers grew, which made it look like a real garden inside this residential area.

For a long time the couple had wanted to build their own house, a neutral house like a blank canvas with nothing to distract their way of living or raising their children. They rejected the idea that a house should represent economic power and attract attention. Their house had to be much more spiritual, a place for balancing the mind and relaxing the body. The dialogue between the clients and the architect never included the word ‘cosy’ or the outmoded phrase ‘home sweet home’. They were much more interested in building a house that would help them prepare their children to go out into the world. Sooner or later the children would leave the nest, so it did not make any sense making things so nice and cosy as to create nostalgia. When Sejima first asked Miyako what kind of a house they wanted, she told her: ‘Something like a temporary perch’.

The architect’s interest arose immediately. Kazyuo Sejima had studied architecture at Japan’s Women University, which had been created after the 2WW as a reaction to the Japanese laws prohibiting women access to state universities. Obviously, the origin of this university centre kindled an attitude of questioning pre-established norms and conventions that had been taken for granted throughout history. In the case of Sejima, observing people’s lifestyles, she questioned the validity of a conventional dwelling that consisted of a set number of bedrooms, a living room, a dining room and a kitchen. Fixed concepts were no longer valid in a rapidly changing society.

A house is “refuge for the mind“

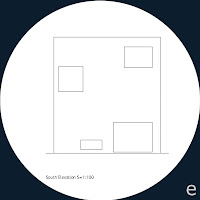

The house appears as a white closed cube as it is located in one of the corners of the site. The door is fused with the wall, the doormat and a small cantilever being the only signs of its presence. Furthermore, instead of conventional windows, a few flat, square cuts are made on the exterior walls, without any seeming order. The logic comes from the inside. Refusing to create stereotyped rooms with a collection of arranged furniture, Kazuyo Sejima proposed to reduce each room to particular furniture or an action. For instance, the bedroom of the children is composed of one room-bed and a room-table. In that way, 17 different rooms were created, which together were arranged on a 77.68 m2 floor area and distributed on two floors with the tearoom on the roof.

Having such a small surface, it was used to its maximum. The structure of the house is built with steel sheets, which reduces the thickness of the external walls to 50 mm and the interior walls to 16 mm. In that way, the structure, walls and the floors merge together and each part appears to have the same weight.

Interpreting the idea of ‘a one room studio’, the architect connected the individual rooms. She made cuts in the internal walls of the adjoining rooms, and left them without any glass. This offered new possibilities. Some rooms look outside through another room’s window. The air flows freely through these openings from room to room, and the boy or his cat can enter or exit through these openings at will. No space is shut off completely. Consequently, offering such a choice of different actions, the idea of privacy turns elastic. The members of the family can choose their place according to their moods, wanting to be alone or with others.

This house links to Sejima’s research about the built contemporary house in our information society. For her, information society is mainly about not seeing. That is, the definition between spaces rather than marking boundaries. It is about creating transparencies in planning the house with non-transparent materials, as she did, for instance, in the daughter’s room where the feeling for depth is eliminated. Here, one can look into the next room through the opening in the steel wall, which is finished in such a way that it makes the room itself look flat, like a suspended image against the wall. When a passer-by walks by the window, suddenly the space between the window and the opening in the wall becomes real.

The house in a plum grove is more than a house in a garden. It is a new type of a house that speaks of how the intangible can form part of the project and design.

Captions for illustrations

a. Kazuyo Sejima (b. 1956) had studied architecture at Japan’s Women University, a university centre which questions pre-established norms and conventions. (Photography: SANAA)

b+c+d+e+f. House in a Plum Grove (2003). Plans, elevation and secction.

g. The children’s bedrooms is composed of one room-bed and a room-table (Photography: SANAA)

h. The structure of the house is built of steel panels, the interior walls being 16 mm thick and, the exterior walls 50 mm of which paint with thermal insulation is included. (Photography: SANAA)

i. The 17 little rooms in the house served as a form of experimentation and to gain a one unique interconnected space (Photography: SANAA)

a. Kazuyo Sejima (b. 1956) had studied architecture at Japan’s Women University, a university centre which questions pre-established norms and conventions. (Photography: SANAA)

b+c+d+e+f. House in a Plum Grove (2003). Plans, elevation and secction.

g. The children’s bedrooms is composed of one room-bed and a room-table (Photography: SANAA)

h. The structure of the house is built of steel panels, the interior walls being 16 mm thick and, the exterior walls 50 mm of which paint with thermal insulation is included. (Photography: SANAA)

i. The 17 little rooms in the house served as a form of experimentation and to gain a one unique interconnected space (Photography: SANAA)